Research & Consulting

What is Applied Research?

Applied research refers to scientific and systematic inquiry that is undertaken with the goal of solving practical problems or addressing specific issues in real-world settings. The ultimate aim is to generate knowledge that can be directly applied to improve processes, products, or services and solve real-world problems. Applied research often involves collaboration between researchers and practitioners in the field, and the results are intended to have direct and practical applications. The findings from applied research are typically used to inform decision-making, policy development, and the development of new products or services.

Explore Recent Studies

Knightdale affordable housing plan

This report was conducted by the Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) of the University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG) in response to a call for proposals from the City of Gastonia, North Carolina for an affordable housing plan.

gastonia affordable housing plan

This report was conducted by the Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) of the University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG) in response to a call for proposals from the City of Gastonia, North Carolina for an affordable housing plan.

transforming lives in northwest north carolina

This report was conducted by the Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) of the University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG) in collaboration with Goodwill Industries of Northwest North Carolina, Inc.

south carolina legal needs assessment 2022

The South Carolina Access to Justice Commission and the Center for Housing and Community Studies of the University of North Carolina Greensboro, together with their partners the South Carolina Bar and the NMRS Center on Professionalism of the University of South Carolina School of Law, came together to launch this ambitious first-ever statewide civil legal needs assessment. The study team set out to learn about the life experiences of low- and moderate-income South Carolinians, the legal problems they encounter, and the gaps between their legal needs and the legal resources available to them.

COVID-19 VACCINE MESSAGING

This study was conducted by the UNCG Department of Health Education and the UNCG Center for Housing and Community Studies in response to a request from Guilford County Department of Health and Human Services Director. The project includes an extensive review of the literature on vaccine hesitancy, interviews and focus groups with local stakeholders and community members, field surveys at vaccine clinics and door-to-door in ‘hot spot’ neighborhoods, and an online survey with more than 1,700 respondents in the County.

DAN RIVER HEALTH EQUITY ASSESSMENT

This study was conducted by the Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) of the University of North Carolina Greensboro (UNCG) in response to a request from the Health Collaborative, a cross-sector group of residents working together to improve the health and well-being of the Dan River Region. The study reflects a process of community engagement and provides a health equity assessment and health equity report for the Dan River Region, building upon the Danville Pittsylvania County Health Needs Assessment and the Dan River Region Health Equity Report, both conducted in 2017 by the Health Collaborative.

NC LEGAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT

This study represents the first comprehensive legal needs assessment in nearly two decades for the State of North Carolina.

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH

This study was developed by the Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) in response to a request from Build Baton Rouge, the City of Baton Rouge, Healthy BR, and the Mid-City Redevelopment Alliance who are leading the Housing 1st Alliance efforts to solve for affordable housing needs in East Baton Rouge Parish, an area with unique needs, strengths, and weaknesses.

Research Archives

This study was developed by the University of North Carolina Greensboro Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) in response to a request from the Department of Planning and Land Use in New Hanover County. We were charged with gathering community input about their perceptions and opinions on workforce and affordable housing. As part of this process we attempted to find and measure the gaps between the housing needs of workers and low-income residents and the resources available to meet those needs.

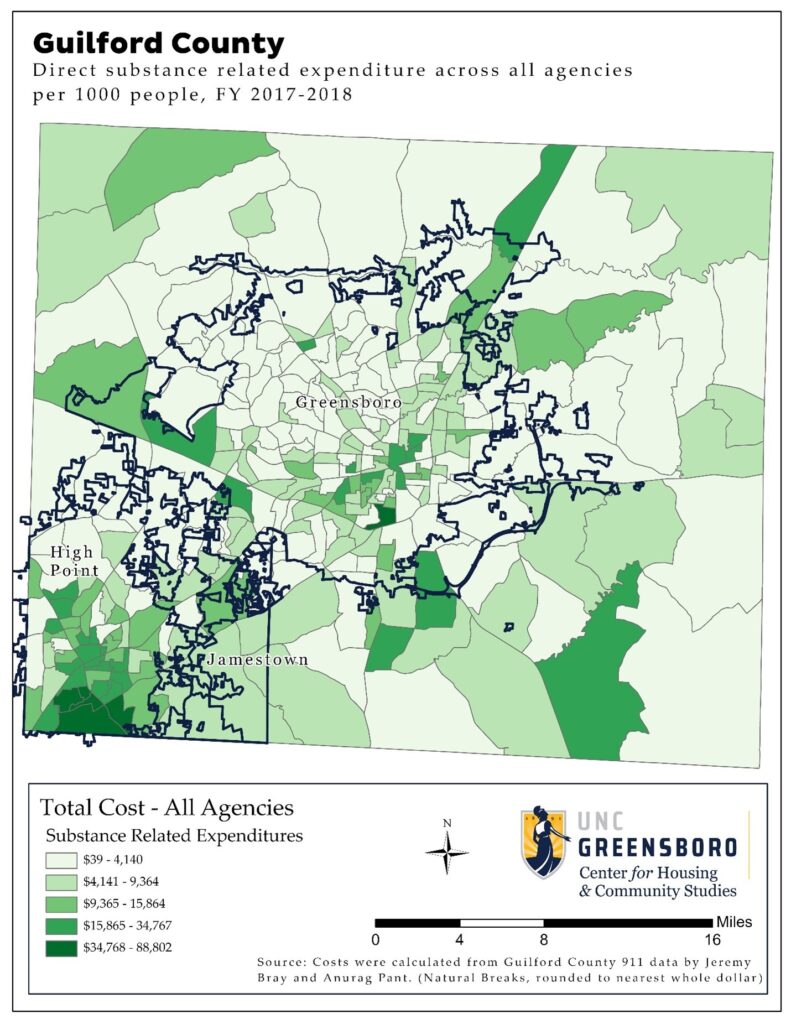

Guilford County is a sprawling urban and peri-urban county in the heart of the Piedmont which includes the Greensboro-High Point MSA as well as incorporated towns of Gibsonville, Jamestown, Oak Ridge, Pleasant Garden, Sedalia, Stokesdale, Summerfield, and Whitsett. It covers an area of 658 square miles and a population of over half a million. It is the third most populated county in NC. It is home to a major airport (Piedmont Triad International), and has a railroad depot located in downtown Greensboro with daily passenger traffic up and down the eastern corridor and in state transportation to Raleigh and Charlotte. The County is home to two major municipalities, Greensboro and High Point, with separate courts, jails and county human services departments in each city. The County is served by three major law enforcement agencies, the County Sheriff’s Department, City of Greensboro Police Department, and the High Point Police Department. The residents of the county and the Guilford County Government have been heavily impacted by substance use. This report was developed by the UNCG in response to a request from Guilford County Government for an assessment of the impact of substance use on the County. The study includes a review of the most recent socio-demographic and economic data derived from local jurisdictional data, proprietary data sets, and state and federal sources.

The study demonstrated the high cost of alcohol and substance use at the neighborhood level in Guilford County in terms of elevated crimes, negative health impacts, loss of life and diminished longevity, and both direct and indirect economic costs. Mapping of substance-related service calls, crimes, overdoses, and deaths provided a clear indication of specific neighborhood-level ‘hotspots’ where alcohol and substance use disproportionately impact residents. Regression analyses also helped to indicate statistically significant factors that contribute to higher county service utilization when controlling for demographics, education, neighborhood economic conditions. In multiple models we saw that crimes (violent, property, and other) were significantly related to increased utilization of county services. Density of alcohol outlets was significantly related to overall utilization of county services and criminal activity, but not statistically related to substance use service call. The overall projected estimated cost burden of substance use to Guilford County was computed at $47,967,241.

CHCS recently developed a health and community “report card” for the Foundation for a Healthy High Point. This report card provides performance benchmarks and improvement targets as it develops programs focused on addressing health needs within the community.

Data in the Health Report Card was sourced from local hospitals and health care providers, county and state public health agencies, as well as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and other federal sources providing the most up-to-date and reliable information available. Drawing from these local, state, and federal sources, over 70 social, demographic, economic, and community health indicators were assembled.

“Each variable was examined as it related to our Intersectional Health Model which includes indicators of personal health management, disease and illness conditions, access to health resources, health behavior engagement, social determinants of health, as well as environmental factors,” says Dr. Gruber. “We settled on fifteen key indicators ranging the life course from birth to old age that demonstrate key public health issues specifically impacting neighborhoods in High Point. Additionally, community health assets were listed and mapped. The resulting profile provides a “picture” of health needs, health behaviors, and health resources available in Greater High Point. The data profile established by this approach provides a baseline for showing comparative progress for the future.”

The Healthy High Point Asset & Health Indicator Map was also created for the Foundation by Dr. Sills and the UNCG Center for Housing & Community Studies. The asset map examines locations of local “assets” (health and health-related facilities) in order to connect the community with resources.

Community Needs Assessment

The High Point Resilience Action Group is an alliance of public, private, and non-profit organizations collaborating to develop integrated infrastructure that empowers all individuals and families to thrive.

Resilience High Point aims to:

- ADDRESS income disparity by workforce development and education training.

- ADVOCATE for expanded and enhanced transportation systems.

- PROVIDE mental health and resilience (trauma) training to any service provider.

AN ASSET BASED COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PLANNING PROJECT

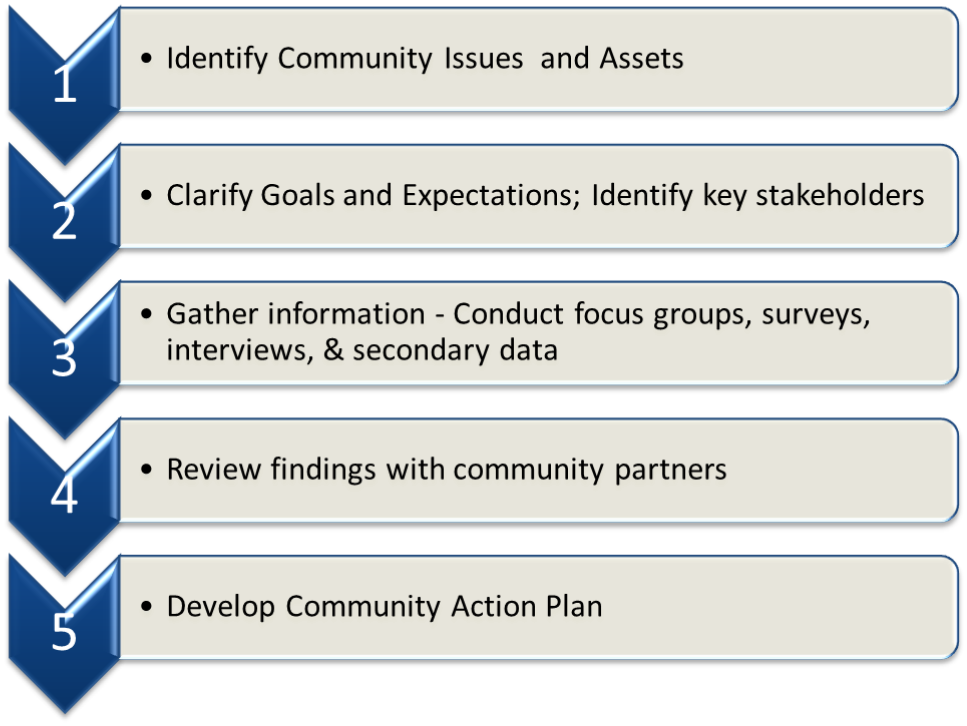

In 2016, The Hinton Rural Life Center in Hayesville, NC, in partnership with a number of community organizations, engaged in a project known as the “Partnering for Change” initiative. The Hinton Center contracted with the Center for Housing and Community Studies (CHCS) at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro to:

- provide technical assistance to the project;

- analyze geographic, economic, and demographic data on the region and its inhabitants;

- conduct focus groups, a multi-modal resident and client survey, and interviews with “key informants” to identify strengths and issues;

- gather and compile a database of community assets;

- produce an online GIS map of community assets; and

- conduct a Community Action Planning session to review findings and brainstorm solutions.

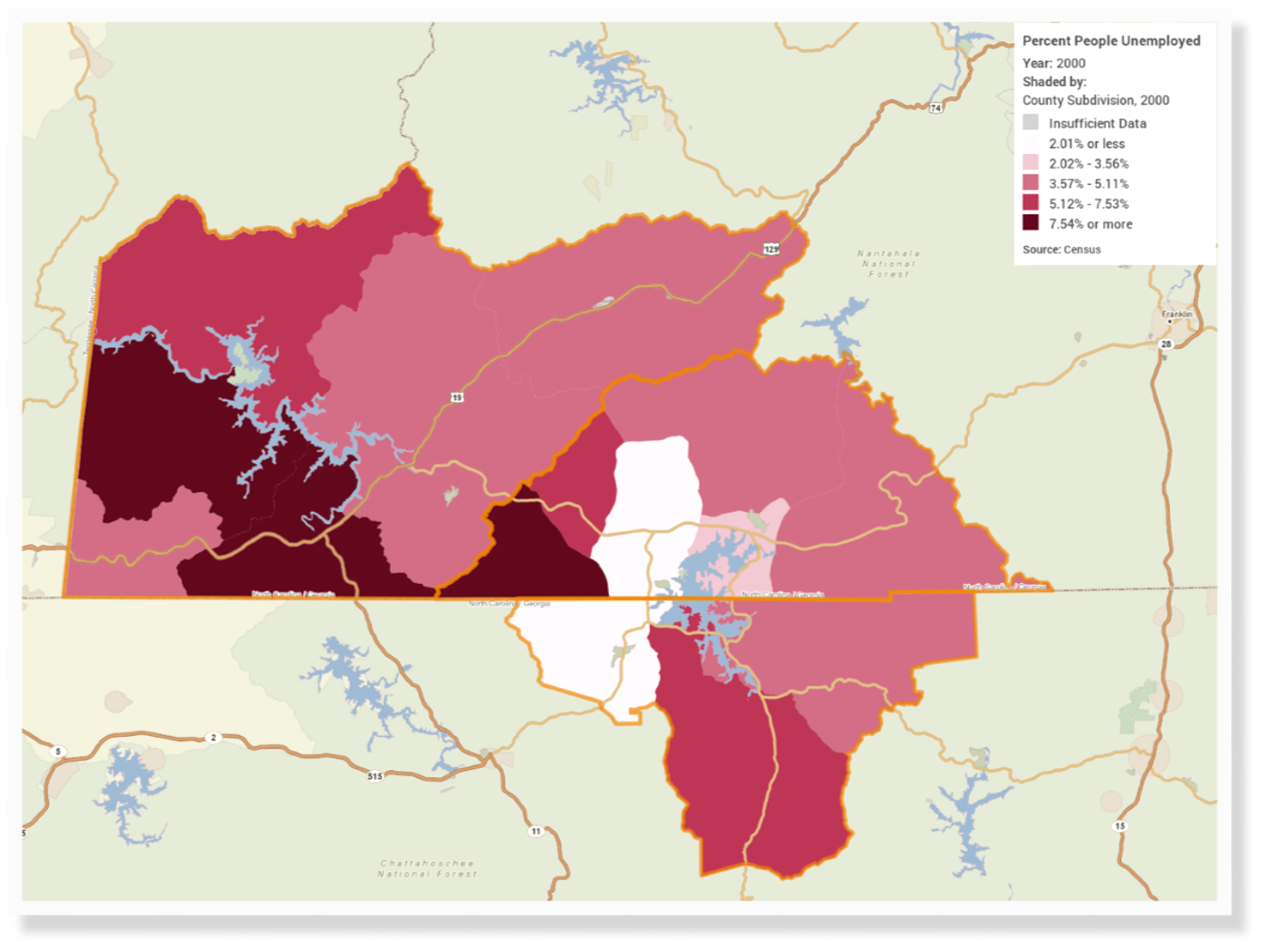

Over the course of 10 months (March 2016 to January 2017) the Hinton Center, The Center for Housing and Community Studies, and community partners examined the quality of life in Clay, Cherokee, and Towns counties. Eleven focus groups, 573 surveys, and 26 interviews were conducted assessing satisfaction in community members’ lives regarding physical health, family, education, employment, finances, environment, and more. Contributions were submitted by clients, service providers, community leaders, and citizens to the Community Asset Map in order to identify resources currently available for enhancing the quality of life and to expose gaps in service systems.

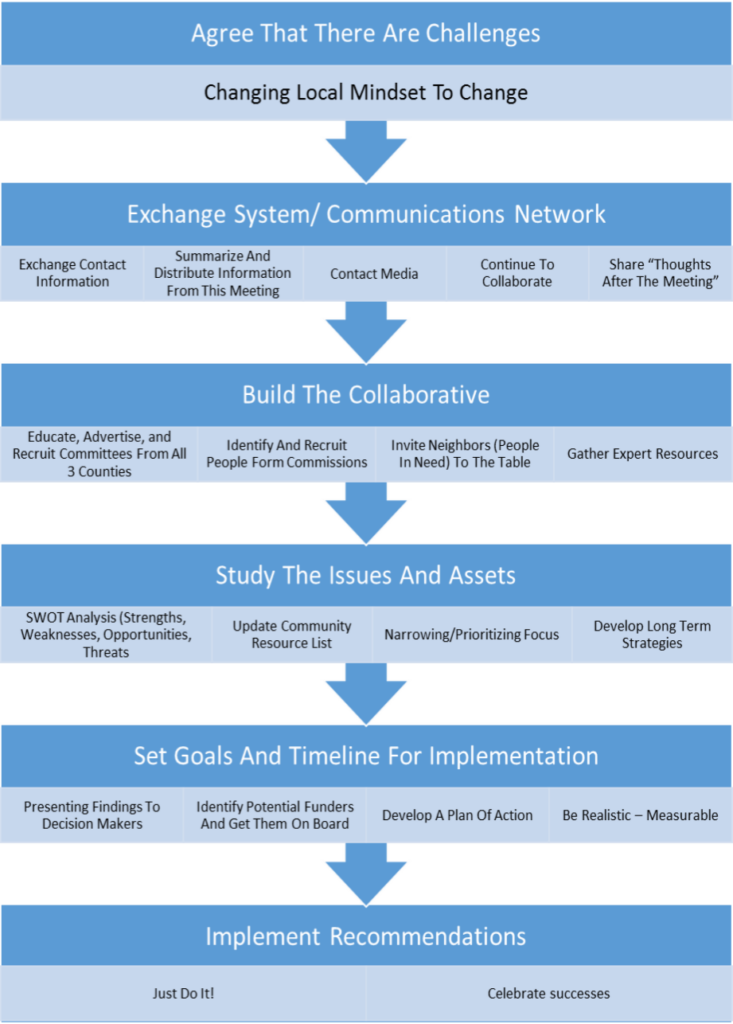

The mission of the project was to identify, collect, and share this data and to build relationships and networks that will enhance collaboration. The project is intended to establish an inter-agency collaborative and Community Action Plan (CAP) for the three counties. Ultimately, the goal is to improve the quality of life for all residents by enhancing opportunities for economic development and by finding ways to solve community concerns. Through a series of workshops with the “Partnering for Change” executive committee, the initiative developed a vision of the future that would address the issues impacting the community and result eventually in a “Thriving community with opportunities and choices for a better quality of life for all.” The Community Action Planning (CAP) process resulted in a set of recommendations and ‘next steps ’aligned with achieving this vision.

The mission of the project was to identify, collect, and share this data and to build relationships and networks that will enhance collaboration. The project is intended to establish an inter-agency collaborative and Community Action Plan (CAP) for the three counties. Ultimately, the goal is to improve the quality of life for all residents by enhancing opportunities for economic development and by finding ways to solve community concerns. Through a series of workshops with the “Partnering for Change” executive committee, the initiative developed a vision of the future that would address the issues impacting the community and result eventually in a “Thriving community with opportunities and choices for a better quality of life for all.” The Community Action Planning (CAP) process resulted in a set of recommendations and ‘next steps ’aligned with achieving this vision.

Multi-Step Data Collection Process

Techniques such as surveys, visits, and resident involvement are used commonly in ABCD and have been helpful in this project by enabling us to find resources within both formal and informal networks. This project involved a mixed-method design including qualitative focus groups to establish the key concerns of different segments of the community, followed by an online and paper survey of residents, and concurrent interviews with key-informants and community leaders. Review of best practices literatures, compiling of secondary data, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping and analysis, and qualitative analysis of focus groups, community meetings, and key informant interviews was conducted. The participatory process for the development of data collection instruments with the “Partnering for Change” leaders allowed for identification of relevant items from the literature as well as obtaining input from members of the community on most important issues. This design provides the greatest validity and reliability. In all, the UNCG- CHCS project team has:

- Collected secondary data on the region and produced a “snapshot” report on social, economic, and demographic issues;

- Compiled a database of assets and created an online interactive GIS map;

- Conducted 11 focus groups,;

- Developed a multi-modal resident and client survey (online and paper, n=573);

- Conduct telephone interviews with 26 “key informants”

- Provided three training workshops; and

- Conducted a day-long Community Action Planning retreat.

More on this project including documents, workshop handouts, and interactive asset map may be found at the Hinton Quality of Life Study page at: https://www.hintoncenter.org/quality-of-life/

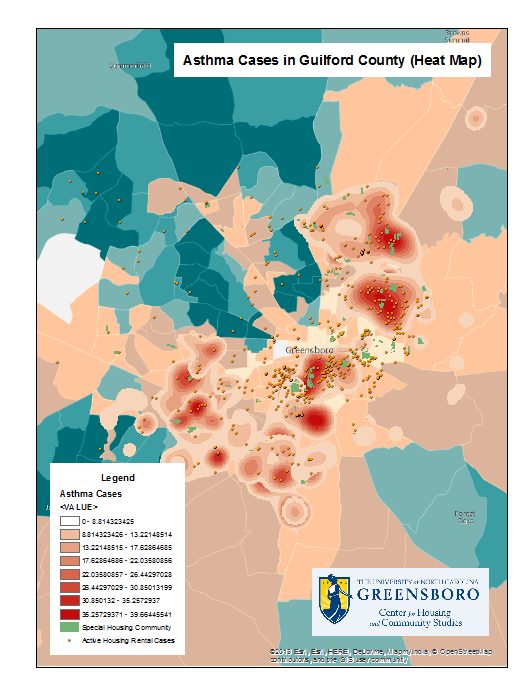

Greensboro is one of 50 cities selected to take part in a new, national community health focused initiative. As part of the program, Greensboro will address the city’s pediatric asthma rate, which disproportionately affects low-income children.

Invest Health, a collaboration of the Reinvestment Fund and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, aims to transform how leaders from mid-size American cities work together to help low-income communities thrive, with specific attention to community features that drive health, such as access to safe and affordable housing.

A team representing the City of Greensboro, Cone Health, East Market Street Development Corporation, Greensboro Housing Coalition and The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) applied for grant funding to improve the availability of safe, affordable housing for families living with asthma.

The team’s proposal was selected from 180 proposals representing 170 different cities across the nation. Over the next 18 months, Greensboro’s Invest Health team will receive a $60,000 grant, take part in a vibrant learning community and have access to highly skilled faculty advisors and coaches who will guide their efforts toward improved health.

“Greensboro’s asthma rate is influenced by higher than average poverty and uninsured rates,” explained Dr. Stephen Sills, director of the UNCG Center for Housing and Community Studies.

More than 19,000, or 29.3 percent, of children in Greensboro live in households below the poverty level, and a majority of those homes are not safe for children with asthma.

“These families have few options in terms of affordable and healthy housing, which consigns over 6,000 children with asthma to live in places that make them sick,” Sills said. “Strong evidence has linked plumbing or roof leaks, inadequate ventilation, faulty or inoperative exhaust systems, unclean floors and other surfaces, presence of rodents or cockroaches and building structure issues to subsequent asthma incidence and morbidity.”

Mid-size American cities face some of the nation’s deepest challenges with entrenched poverty, poor health and a lack of investment. But they also offer fertile ground for strategies that improve health and have the potential to boost local economies.

“Our goal is to transform how cities approach tough challenges, share lessons learned and spur creative collaboration,” said Amanda High, chief of strategic initiatives at Reinvestment Fund.

Greensboro’s Invest Health projects will explore a broad range of ideas, from leveraging relationships with the health system to connect affected patients’ families with community action planning, to aligning Invest Health efforts with existing housing improvement projects such as Housing Our Community.

The local team is represented by Cynthia Blue, City of Greensboro; Rev. Beth McKee-Huger, a community housing advocate; Kathy Colville and Jasmin Hainey, Cone Health; Dr. Patrick Wright, Cone Health Medical Group; Mac Sims, East Street Market Development; Brett Byerly, Greensboro Housing Coalition; Dr. Tom Wall, Triad HealthCare Network, and Dr. Kenneth Gruber and Dr. Stephen Sills, UNCG. More on the team is available at https://www.investhealth.org/teams/greensboro-nc/

The Greensboro team has been working on five interrelated sub-projects:

- A process to identify children with asthma in housing with environmental triggers associated with asthma;

- An initiative to inform the health care system about substandard housing and asthma;

- Data-driven targeting of housing repair and rehabilitation programs in high-need neighborhoods;

- Recommendations for redevelopment funds to be used on multifamily properties that have conditions which exacerbate childhood asthma; and

- A collaborative network that prioritizes community health in City planning.

We are focused on a neighborhood demonstration project before scaling citywide. Our challenges have been many: how to access patient level hospital data, how to involve the healthcare system directly in the project beyond access to data, how to fund interventions on a household level, how to balance the needs of the City government to remain business-friendly while also pursuing issues with landlords with substandard properties, how to leverage enough funding to rehab/redevelop properties in areas where the market will not support it, and how to work with property owners who will not fix substandard housing.

Guilford County, North Carolina is home to a wide range of agricultural resources, including 90,750 acres of farmland and $685,000 in agritourism and recreational activity . At the same time, Greensboro/High Point, the major metropolitan area within the county, has 24 food deserts , a food insecurity rate of 19% , and the highest food hardship rate in the United States . Considering this disconnect between local food and agriculture resources available and the use of those resources by individuals, families, and institutions, the City of Greensboro has mobilized several stakeholders to promote food security across our communities and develop mechanisms that support individuals and organizations who start businesses around local foods.

The City of Greensboro, the Greensboro Community Food Task Force, and the Guilford Food Council have been working together to promote food security across the Greater Greensboro Metropolitan Area and tackle the issues of access to healthy food and economic development around local food businesses. In 2014, with funding from U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Local Food Promotion Program (LFPP) Planning Grant these organizations, and other community partners, developed a Fresh Food Access Plan which was adopted by the City in 2015. This plan identified Gaps in Our Food System, Barriers to Food Access, a lack of distribution opportunities for local Farmers and a need for commercial kitchens which would promote new food business development. The USDA has since awarded the City a Local Food Promotion Program (LFPP) Implementation Grant to help fund portions of a food plan.

The USDA awarded the City a Local Food Promotion Program Implementation Grant to help fund portions of a food plan. The City is working with four primary partners on the program: Guilford County Cooperative Extension Office, the Greensboro Farmers Market, the Out of the Garden Project, and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro Center for Housing and Community Studies (UNCG-CHCS). The City is leading in administering the funds and coordinating efforts among the partners, now known as Kitchen Connects GSO. The project addresses the lack of shared kitchen space for new local food entrepreneurs which was a recommendation of the 2015 Fresh Food Access Plan (page 33).

The LFPP funding is intended to support the expansion of local food entrepreneurs and provided them with connections to local producers; enable local growers to create value-added food products; provide a model for working with a neighborhood to increase the consumption of local produce; and provide data that monitors program results and a reveals clearer picture of local eating and shopping habits. This project anticipates the development of new market opportunities for food businesses and support for local food producers by:

- by providing food safety training and certification classes for local farmers and food-based entrepreneurs;

- providing training and marketing space for new businesses;

- increasing domestic consumption of locally produced agriculture by connecting local entrepreneurs to local producers at the Greensboro Farmers Market;

- increasing access to locally produced food by modeling a program to support food education and food businesses in a low-income neighborhood with limited food access;

- assisting in the expansion and development of other food business enterprises by providing statistically valid surveys to analyze food hardship the local food supply and demand in Greensboro and the effect this program has:

Four objectives have been identified for the implementation and evaluation of this program:

- Objective 1: Create and coordinate resources for local food businesses.

- Objective 2: Create demand for local produce converted into a shelf-stable product.

- Objective 3: Decrease the barriers for local farmers that want to diversify from commodity crops to locally consumed crops.

- Objective 4: Assess the use of local food resources by consumers, including those provided through the proposed program.

The UNC Greensboro Center for Housing and Community Studies served as the evaluator for the implementation program (aka Kitchen Connects GSO). Annual evaluation reports are available below:

RENTAL HOUSING DISCRIMINATION OF LGBTQ HOME SEEKERS IN GREENSBORO: A FAIR HOUSING STUDY

Joyce Clapp and Melissa Roberts, Project Coordinators

In January 2015, Greensboro city council members voted unanimously to add protections for sexuality and gender identity to the city’s Fair Housing Ordinance. Greensboro is the first city in North Carolina to protect gay and transgender citizens from discrimination in housing. The ordinance adds to gender, gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation to the other federal protected categories already in place. This proposal outlines a project to audit rental housing in Greensboro for discrimination of same-sex couples. There is very little research (national or local) in the area of housing discrimination by sexual orientation. Friedman et. al. (2013) found evidence that “housing providers are less likely to respond to same-sex couples than to heterosexual couples” in online solicitations for rental housing, yet there is little data available beyond this study. It would be very beneficial to have baseline data for the City of Greensboro as these new ordinances are implemented. Our past studies have shown that these violations occur in up to 30% of rental transactions. This project seeks to document the incidence and prevalence of LGBTQ housing discrimination and to use this data to educate landlords and property managers. As discriminatory practices are exposed and ameliorated, housing choices for LGBTQ and minority home-seekers will be improved.

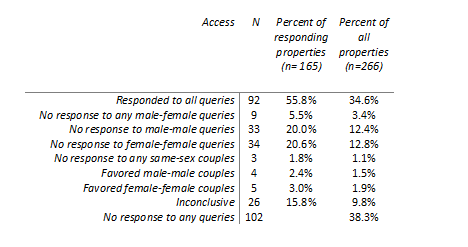

Fair housing testing in Greensboro has never before been conducted for sexual orientation or sexual identity discrimination. This study examines housing discrimination against the gay and lesbian couples. The study took place in two phases to gauge the prevalence of sexual orientation discrimination by housing providers in Greensboro, and then to pilot a protocol for face-to-face paired testing. In phase one, a correspondence test with nearly 266 properties was conducted to establish the prevalence of sexual orientation discrimination by landlords and property managers noting discrepancies in access, cost, information, and encouragement when possible. The second phase included 5 face-to-face paired testing and serves as a pilot for eventual audit testing of rental housing on the basis of sexual orientation. Each tester received a stipend of $50 for each completed test. To ensure consistency and accuracy, data from report forms were then compared line by line against tester narratives. Funding received from the Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creativity Office at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro was instrumental in the completion of the correspondence phase. Funding received from the Human Relations Department at the City of Greensboro was instrumental in the completion of this phase.

Phase I

In sum, rental inquiries were made by email or online contact forms to all 266 housing providers in Greensboro for whom a means of online contact was available. A database of all known providers of rental housing in the city of Greensboro was created in preparation for this project. This database began with an existing list of already known housing providers in the city, which included individual landlords, apartment complexes, and property management companies. All housing providers received inquiries from the same email accounts representing the same fictitious couples in the same order.

Access

Overall, 38.0% of properties did not respond to any correspondences. Yet, the 165 properties to respond to at least one of the solicitations (email or online form), generated a total of 661 email responses. In all, 92 properties (55.8% of responding properties) showed equal access for all couples. A third of responding properties (52 total) did not respond to all queries. Of these, 9 did not respond to male-female inquiries: 4 of those favored male-male couples by responding only to them, and 5 favored female-female couples only. Thirty-three properties (20%) did not respond to male-male inquires, and thirty-four properties (20.6%) did not respond to female-female inquires. About 15.8% (26) of responses were inconclusive.

Costs

A variety of measurements of cost were recorded including fees related to lease initiation (application fees, administrative fees, other fees) and monthly fees (rent, any included utilities, etc.), as well as any specials offered to the fictitious couples. In determining equality of costs quoted, all measurements of costs were considered. Thus, housing providers who indicated different rental ranges for different couples, or advised of a special to waive administrative fees for some but not all couples, were indicated as providing unequal costs to couples. In all, 7.9% (13) apartments quotes the same or equal information to all inquiries. Most properties, 82.4% (136), were indeterminate with costs not provided to everyone. Finally, 9.7% (16) properties clearly provided unequal costs to inquiries.

Information

Information provided was gauged based on housing provider response regarding availability, rental qualifications, and unit information (number of bedrooms/bathrooms, etc.) A variety of measures were considered in determining the qualifications noted, including mentions of credit checks, background checks, fees, income, and references. Providers who gave different information to any of the couples on any of these measures were coded as providing differential outcomes.

Encouragement

Multiple variables were considered in measuring encouragement provided to each couple, these included follow-up, and offers of inspection and contact. Regarding follow-up, the number of emails/follow-ups sent from housing providers to each couple were reviewed; housing providers who made further attempts at contact with some couples but not all, as gauged by the number of emails sent, were found to have provided differential encouragement. Offers by housing providers to inspect the (tour) the property, or to make contact by calling the provider or coming to the office were also compared across couples for each housing provider. In all, 55.8% of tests showed equal encouragement. Two-in-five tests (40.0%) were inconclusive in terms of encouragement. A small fraction (1.8%) of cases showed less encouragement for male-female couples, while 1.2% showed less encouragement for all same-sex couples. There was a single case (>1.0%) that showed less encouragement for male-male couples and likewise one case (>1.0%) showed less encouragement for female-female couples.

Phase II: Face-To-Face Testing

Phase II of the study consisted of a pilot test or face-to-face testing for five housing providers in Greensboro. As in correspondence testing, four couples each comprised of two testers (two female/male; one male/male; one female/female) visited each selected property. Testers received a small stipend of $50 for each completed test, as well as for required tester training.

Properties tested for the Phase II pilot study were randomly selected from those with differential rates of access in Phase I. Each test cycle began with an Advanced Call made by the Testing Coordinator to confirm availability and obtain basic information about any available units. Once availability was confirmed, the four tester couples were provided with the name and basic information for each property, a requested rent range (which remained the same for all couples) as well as the suitable time-window for testing.

Access

Typical measures of access for fair housing studies center around the access or lack of access to housing providers by housing testers: whether partners were able to call agents, meet with agents, inspect the advertised housing unit and/or other units. For Phase II of this study these same measurements were used. None of the couples for our housing tests faced difficulties in obtaining access to housing providers; for all five properties, all measures of access were granted to all couples making inquiries. No differential access outcomes were observed for any of the five tested properties regardless of condition tested.

Cost

Data collected regarding quoted costs included: application fees, credit check fees, security deposit, monthly rent, and any other fees noted (such as cleaning, administrative, or other fees). Generally, all couples were provided the same costs during tester audits. However, there were several discrepancies. Regarding application fees, two properties provided information regarding promotions and fee reductions to some, but not all, couples. Housing provider basis for determining security deposit amounts, and the upper range of possible security deposit, varied to some degree in one test. All couples received the same information regarding credit check fees, and review of questionnaires, narratives, and additional materials related to other fees also appears to indicate no differences in these quoted costs between couples.

Information

Comparison of information provided to testers included that related to availability as well as qualifications. Regarding availability, testers recorded whether the agent indicated an apartment was available on the date, and the size and price requested. All couples across all tests were advised that an apartment was available. Data was also collected from verbal information provided to testers regarding requirements for rental, including: amount of income, credit qualifications, employment background, rental background, criminal history or background check.

Encouragement

Measures of encouragement included variables related to the initial contact with agent, inspection of unit(s), and agent follow-up. These were measured via data on couple wait times, whether they were asked to complete an application during the audit, whether they were offered the opportunity to inspect applicable units, if agent stated they may be ineligible to rent, and whether they were asked about a follow-up from the agent. All couples across all tests were advised that an apartment was available, minor variation occurred with wait time, encouragement to complete an application, ineligibility, and request to follow-up.

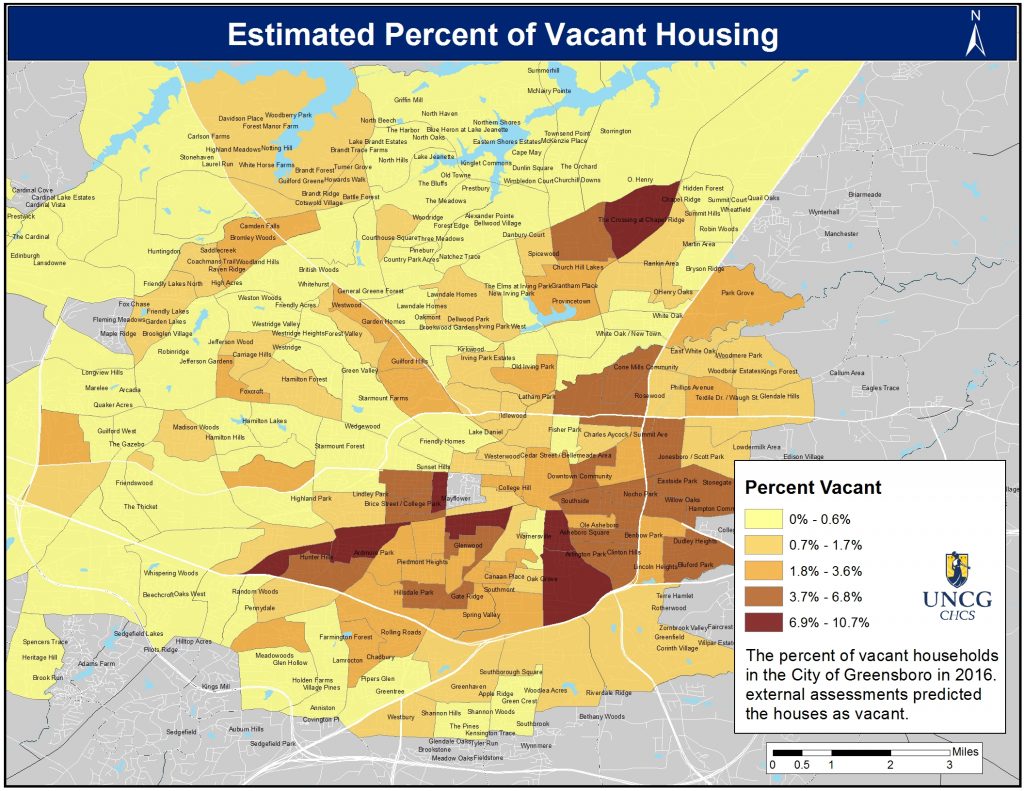

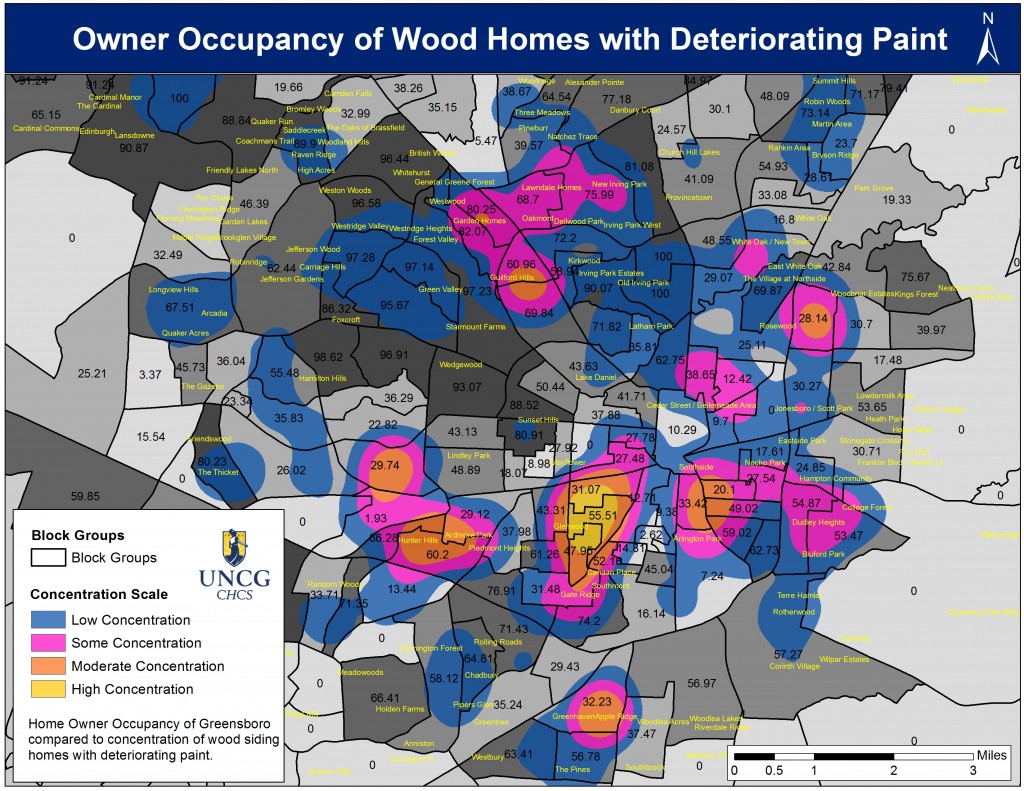

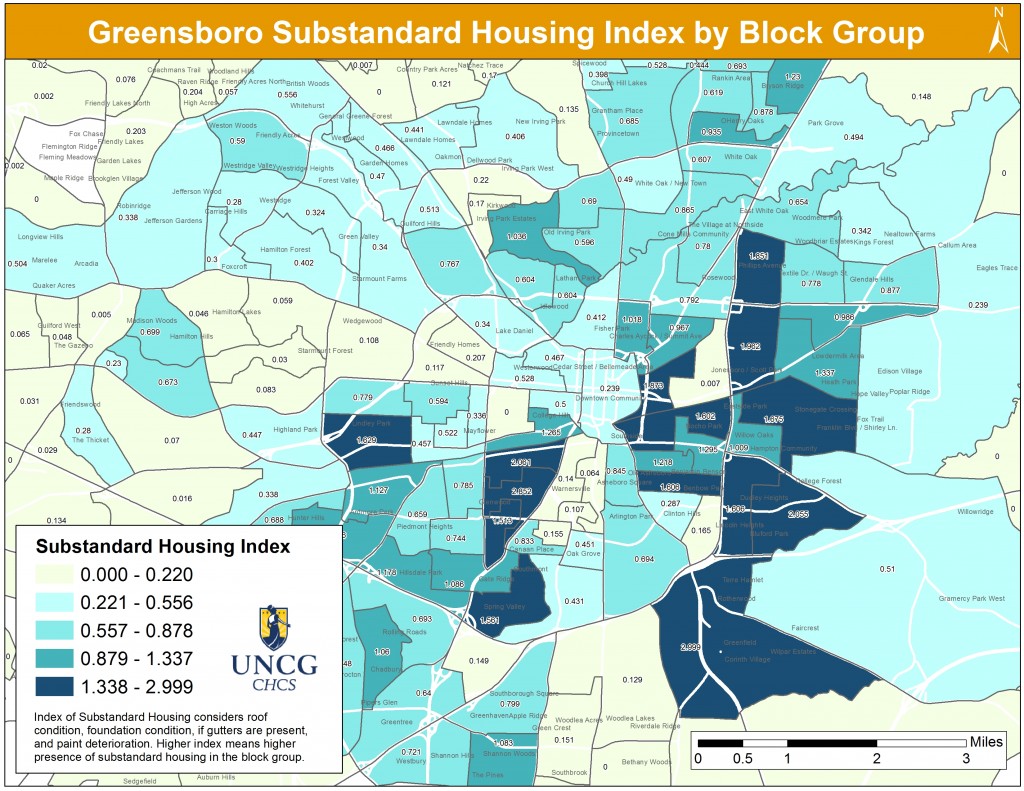

One problem with studying vacant, abandoned, and substandard properties is that many communities have no reliable way to keep track or assessing the conditions of these properties. It is hard to quantify the costs of such properties when there is no central mode of determining the scale and scope in a given area. This project involved the collection of primary data on all land parcels in in the City of Greensboro to determine the frequency of vacant, abandoned, and substandard properties in a neighborhood.

A remote visual inspection of more than 75,000 parcels was conducted using Loveland Technologies Site Control Software tailored to an external assessment survey developed by CHCS. This tool was constructed using the HUD Housing Assessment Instrument, National Center for Healthy Housing recommendations, and local code enforcement standards, as well as assessment tools from local community non-profit housing advocates. Research support staff, overseen by the Director and project coordinator, used this tool to conduct remote visual assessments that were then mapped and layered with additional data from the City of Greensboro, Guilford County, as well as state and federal sources.

Housing quality is an issue for Greensboro residents. Single-family homes in Greensboro are on average over 50 years old, while multi-family homes or apartments are about 35 years old. Waves of development over the years can be seen, with homes built in the 1950s or before concentrated in the city core and the most recent development (post-1988 in the outermost suburbs). Aging housing stock itself is not an issue, if kept up. However, the trend with aging rental housing is for owners not to reinvest in maintenance but to extract whatever rents they can while depreciating the property on their taxes and then speculating on the future resale value.

We have visually assessed more than 75,000 properties. Over a third (35.8%) of the properties surveyed had some sort of issue with the lot – grass or weeds over a foot high and needing mowing; shrubs obscuring the building and needing trimming; trees hanging over roof; inoperable vehicles on the lawn or drive; substantial trash or debris in the yard; building materials, tires, automotive parts, or appliances, in the yard; or dangerously low-hanging power lines. While some of these code enforcement issues are simply a nuisance, unsightly properties due impact property values of adjacent property and can lead to potential health and safety issues.

Looking at major structural conditions like roof, windows, foundations or as a composite statistic of all of these features together, then determining – relative to other properties what is the condition of this home. Our scale is 18 points with higher being better condition. The ‘average’ house in Greensboro for which we collected all of this data, is 16.39. The lowest score had poor windows, poor siding, poor foundation, poor roof, poor paint, had no gutters, and may be fire damaged. Properties with a score of 14 are a standard deviation below the mean , 13% of properties are a standard deviation below average. Properties with a score of 12 were two and a half standard deviations below the mean, 4.2% of properties were in this category.

Studies have shown that substandard housing is clearly related to increased likelihood of health concerns and mental health issues.

Specific health hazards of substandard housing including: frequent changes of residence (community instability), mold from excessive moisture, exposure to lead, exposure to allergens that may cause or worsen asthma, rodent and insect pests, pesticide residues, and indoor air pollution.

Depression and self-perception of health status are higher for those living in areas of high poverty.

Private investment market cannot take care of all the needs for affordable house in Greensboro. It takes public-private partnerships.

We need to continue proactively and affirmatively promoting fair, healthy, and affordable housing in Greensboro for all. We need more low-cost housing in high opportunity neighborhoods. The evidence from a history of building assisted housing in already poor neighborhoods shows that it does not work.We need mixed income development to be encouraged by policy makers and made real by developers. Yet, we need to be careful about gentrification.