Accessory Dwelling Units Won’t Dent the Affordable Housing Crisis.

ADUs are buzzy, they’re attractive, they’re problem solvers, they represent a zoning reform that might be achievable and might actually add some affordable housing units, and all without really having to challenge the prevailing order. But how much good it will really do in the end, is the subject of this post.

A 2008 HUD publication offered a definition that seems to have stuck: “additional living quarters on single-family lots that are independent of the primary dwelling unit.” The ADU may be attached to the main house, or a part of the main house’s interior, for example in the basement or a converted garage, or it can be a free-standing detached structure, or it can be above the detached garage. They can be very appealing, being less expensive to build than a conventional single-family dwelling and able to utilize an excess portion of the existing lot. ADUs can bring in rental income or provide a home for an in-law or aging parent, or an aging child for that matter just entering the workforce, helping cities adapt to the changing needs of multigenerational households. Before World War II, “they were a common feature in single-family housing,” but as low-density suburban landscapes captured – and stultified – the American imagination, ADUs were outlawed in one town after another. Increasingly, insisted the purists, single-family meant single-family!

In this post we’ll review recent developments, which have positioned the ADU as a new-old way to increase the stock of housing in neighborhoods traditionally resistant to innovation and added density. But first, let’s look at this resistance. That so much effort and controversy is being devoted to what is an extremely modest set of reforms is evidence of the sacrosanctity of single-family zoning in America. Let’s look at that.

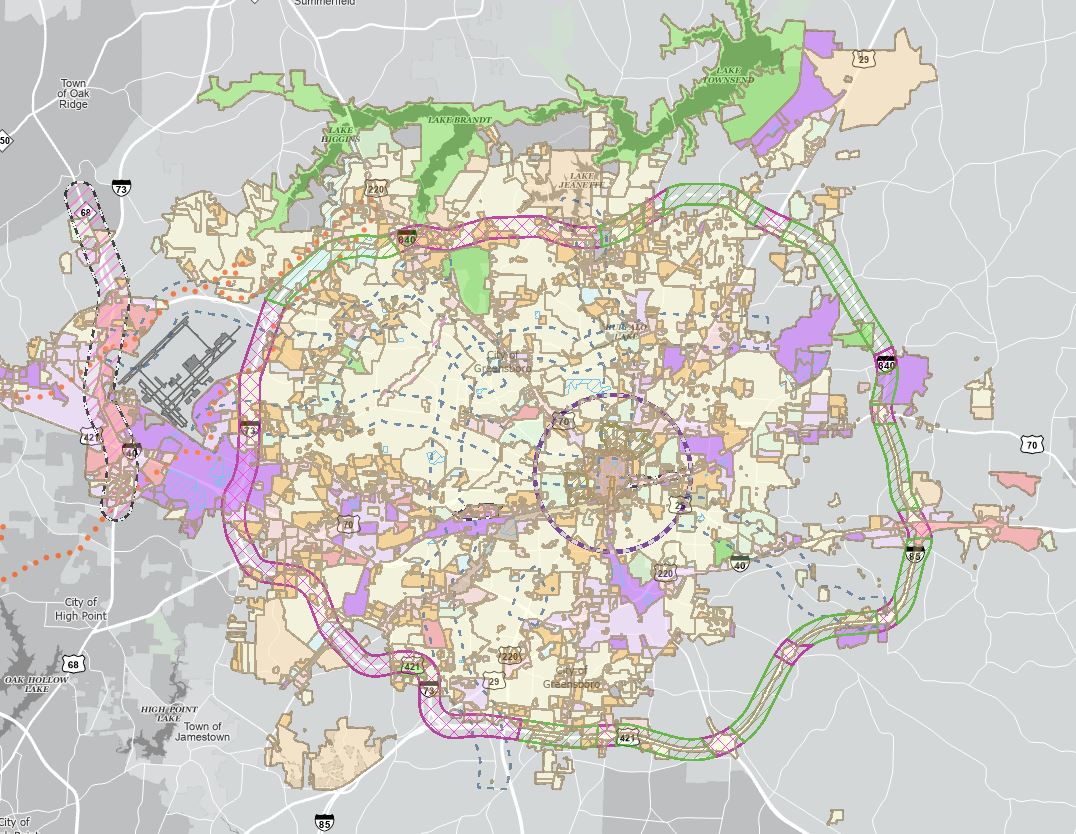

Single-family residential is the predominant land use in American cities, so what’s allowed there makes a big difference. In Greensboro this is visibly the case: the pale tan color on the zoning map shown at the top of this page is single-family residential – by far the largest zoning distribution category. In some suburban centers, the percentage “approaches ubiquity,” and even some big cities like Charlotte and San Jose exceed 80% single-family. In a single-family zoning district, no other structure than a detached single-family home may be built, not an apartment building, and more to the point, not even an apartment for grandmother.

Americans began as early as 1900 to think of multifamily residential buildings as inimical to good citizenship, conducive to drink, and downright evil. That view was memorialized forever by the Supreme Court in the landmark case that established the modern zoning system, setting the tone for generations when it called the apartment house “a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district.” Ever since, a single-family home has been a signifier of middle class status and the achievement of the American dream, and ever since, homeowners have appeared at rezoning hearings to denounce apartments in terms at least as inflammatory and inaccurate as those used a hundred years ago.

The critique, too, is a hundred years old. The single-family housing model was denounced then as an American fetish, and denounced last year as “the most inequitable and environmentally destructive practice in North American planning.” The Biden administration has taken steps to eliminate it. Today, the critique is two-fold. First, single-family zoning promotes segregation and wealth inequality. By limiting access to neighborhoods and even to entire cities to those able to purchase large and expensive dwellings, it excludes low- and many middle-income people. Public policies that inflate home values make homeowners happy but homes unaffordable to everyone else. In this way, single-family land use “has been weaponized against those members of society with the fewest resources.” Second, it exacerbates the climate crisis through reliance on inefficient and wasteful building types and high rates of automobile use to connect homes located far from commercial centers.

This dismal record on our two most acute social challenges explains the rising chorus of voices seeking zoning reform. Some proposals are sweeping, but some seek just modest increases in housing density, and of these, the ADU reform should perhaps be the least offensive. The ADU more than any of the alternatives leaves unchanged the single-family character of the neighborhood, with ordinances limiting the size to a fraction of the main house’s floor area, requiring additional off-street parking, ensuring the property maintains a single-family appearance from the street and, sometimes, requiring the ADU match the materials and style of the main house. Often the owner is required to live in either the main house or the ADU, as a hedge against undesirable renters, and some ordinances limit the number of ADUs on a block.

But the ordinances themselves act as barriers to ADU development. Permitting can be costly and cumbersome; construction, while cheaper than what a full-size house would cost, is still expensive; and an ADU can cause property taxes to rise. When the main objective of ADU ordinances is to calm homeowners’ nerves, the ordinances become too restrictive. Ordinances permitting ADUs aren’t actually uncommon, even in North Carolina – Asheville, Durham, Greensboro, Raleigh and Wilmington have ordinances permitting ADUs – but not many of them actually get built.

Moves to ease the restrictions are not uncommon, either. Wilmington has been debating an expanded ADU ordinance for two years, extending it to all districts, increasing the size limit and easing the parking space requirements, yet fears of unruly renters, greedy investors, Airbnb’s and overtaxed infrastructure have delayed action. Greensboro planners have on occasion promoted greater use of ADUs, but no specific proposal has been introduced.

Restrictive regulation may be only one of several barriers to ADU uptake, and there are indications that, even in places where ordinances are most permissive, ADUs are proving not to be the hoped-for solution to the affordable housing shortage. High on the list of those places would be California, which beginning in 2016 adopted a series of statewide laws mandating liberal ADU regulations in all cities and counties, with streamlined approvals and generous size limits and parking space requirements. This legislation spurred the construction of a significant number of ADUs, as has similar local legislation in Portland, Oregon, yet hardly enough to make a dent in the need. Barriers remain that can’t necessarily be overcome through liberal legislation. Lack of financing, lack of desire, lack of awareness, site limitations and concern about the character of the neighborhood were cited by California homeowners as reasons not to build ADUs. Absent regulatory controls, ADU rents aren’t necessarily affordable. And researchers found that even under the statutory regime, some municipalities found ways to resist ADU development. Some observers are concluding that, notwithstanding the buzz, the ADU ordinances just aren’t going to have much of an impact.

More aggressive measures will be needed. Housing reform that’s invisible and doesn’t actually change anything is destined to fall short. The hallowed tradition of single-family zoning will have to be confronted honestly rather than sneakily. And the roadmap for this confrontation is becoming clear. Cities needn’t abandon density limits; they can move to a medium- rather than a high-density approach. Single-family districts will make room not necessarily for hundred-unit apartment blocks but for the “missing middle” consisting of twins, duplexes, fourplexes and townhouses. These won’t hide behind big single-family homes; they will be visible from the street, but limitations as to materials, density and form will preserve the character of the neighborhoods. This approach really could increase materially the number of dwelling units in a neighborhood, while maintaining the neighborhood’s human scale. None of these building types is allowed in single-family residential districts as they are constituted now, and the purists will fight to keep them out just as they have fought everything else, but reformers are knocking on the door and they are being persistent.

Pathbreaking proposals on these lines have been offered just in the last few weeks here in North Carolina. Bills have been introduced in the House and Senate to mandate liberal ADU ordinances and prohibit regulations that unreasonably block missing middle housing. Sweeping zoning reforms have been proposed in Asheville and Charlotte. With opponents already issuing dire warnings of the end of the American dream, progress will be slow. But gradually, with cities across the country chipping away at it, the edifice of single-family zoning may really begin to crumble.

References

- Applebaum, Binyamin. 2019. “Much Ado About a Little More Housing.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/01/opinion/montgomery-county-housing.html. August 1.

- Baar, Kenneth. 1992. “The National Movement to Halt the Spread of Multifamily Housing, 1890-1926.” Journal of the American Planning Association. 48(1): 39-48.

- Badger, Emily and Quoctrung Bui. 2019. “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: A House With a Yard on Every Lot.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html. June 18.

- Brasuell, James. 2021. “Zoning Reform Skepticism.” Planetizen. https://www.planetizen.com/news/2021/03/112489-zoning-reform-skepticism. March 4.

- Brinig, Margaret F. and Nicole Stelle Garnett. 2013. “A Room of One’s Own? Accessory Dwelling Unit Reforms and Local Parochialism.” Urban Lawyer. 45(3): 519-567.

- California Department of Housing and Community Development. 2021. “Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) and Junior Accessory Dwelling Units (JADUs).” hcd.ca.gov. https://www.hcd.ca.gov/policy-research/accessorydwellingunits.shtml.

- Chapple, Karen, et al. 2020. “AUDs in CA: A Revolution in Progress.” UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation. https://www.aducalifornia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ADU-Progress-in-California-Report-October-Version.pdf.

- City of Asheville. 2021. “Code of Ordinances §7-14-1(b)(3). Accessory dwelling units. https://library.municode.com/nc/asheville/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIICOOR_CH7DE_ARTXIVACTEUSST#:~:text=An%20accessory%20dwelling%20unit%20shall,per%20single%2Dfamily%20detached%20dwelling.

- City of Durham / Durham County. 2021. “Unified Development Ordinance Paragraph 5.4.2. Accessory Dwellings. https://durham.municipal.codes/UDO/5.4.2.

- City of Greensboro. 2021. “Land Development Ordinance §30-8-11.2. Accessory Dwelling Units.” http://online.encodeplus.com/regs/greensboro-nc/doc-viewer.aspx#secid-365.

- City of Greensboro. 2002. “Zoning and Land Use.” Greensboro-nc.gov. https://www.greensboro-nc.gov/home/showdocument?id=8213#:~:text=Single%2Dfamily%20residential%20is%20the,of%20residential%20use%20to%2037%25.

- City of Greensboro. 2018. “City Hosts March 13 Event About Trending ‘Accessory Dwelling Units.’” greensboro-nc.gov. https://www.greensboro-nc.gov/Home/Components/News/News/10327/. March 5.

- City of Raleigh. 2020. “An ordinance to amend the Part 10 Raleigh Unified Development Ordinance to allow accessory dwelling units on lots with existing detached or attached houses.” https://cityofraleigh0drupal.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/drupal-prod/COR22/TC-16-19-ORD.pdf.

- City of Wilmington. 2019. “LDC Update. Accessory Dwelling Units.” https://www.wilmingtonnc.gov/home/showdocument?id=10190.

- Davis, Alyssa. 2018. “The Tiny House Solution: Accessory Dwelling Units as a Housing Market Fix.” Kennedy School Review. https://ksr.hkspublications.org/2018/09/04/the-tiny-house-solution-accessory-dwelling-units-as-a-housing-market-fix/. September 4.

- Fessler, Pirmin and Martin Schürz. 2021. “Housing and the American Dream: Is A House Still a Home?” Institute for New Economic Thinking. https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/housing-and-the-american-dream-is-a-house-still-a-home. February 23.

- General Assembly of North Carolina, Session 2021. House Bill 401. “An Act to Provide Reforms to Local Government Zoning Authority to Increase Housing Opportunities and to Make Various Changes and Clarifications to the Zoning Statutes.” https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2021/H401. March 25.

- General Assembly of North Carolina, Session 2021. Senate Bill 349. “An Act to Provide Reforms to Local Government Zoning Authority to Increase Housing Opportunities and to Make Various Changes and Clarifications to the Zoning Statutes.” https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2021/S349. March 25.

- Gordon, Brian. 2021. “The battle for ‘middle housing’: Asheville Neighbors fight to save single-family zoning.” The Fayetteville Observer. https://www.fayobserver.com/story/news/2021/04/16/north-carolina-single-family-zoning-could-eliminated-new-bills-asheville-housing-affordable/7242807002/. April 16.

- Kahlenberg, Richard D. 2021. “If You Care About Social Justice, You Have to Care About Zoning.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/opinion/if-you-care-about-social-justice-you-have-to-care-about-zoning.html. April 19.

- Lane, Angie. 2020. “Why Everyone Is Talking About Accessory Dwelling Units.” A. Lane Architecture. https://www.alanearchitecturepllc.com/post/why-everyone-is-talking-about-accessory-dwelling-units-adu. June 30.

- Leibig, Phoebe S., Teresa Koenig, and Jon Pynoos. 2006. “Zoning, accessory dwelling units, and family caregiving: issues, trends, and recommendations.” Journal of Aging and Social Policy. 18(3-4_: 155-72.

- Manville, Michael, Paavo Monkkonen, and Michael Lens. 2020. “It’s Time to End Single-Family Zoning.” Journal of the American Planning Association. 86(1): 106-112.

- McKinsey Global Institute. 2016. “A Tool Kit to Close California’s Housing Gap: 3.5 Million Homes by 2025.” https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/Closing%20Californias%20housing%20gap/Closing-Californias-housing-gap-Full-report.pdf.

- Missing Middle Housing. 2021. “Missing Middle Housing.” https://missingmiddlehousing.com/.

- Obrinsky, Mark and Debra Stein. 2007. “Overcoming Opposition to Multifamily Rental Housing.” Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/rr07-14_obrinsky_stein.pdf.

- Praats, Michael. 2019. “Accessory dwelling units, a solution for affordable housing in your own backyard?” PortCityDaily. https://portcitydaily.com/local-news/2019/02/05/accessory-dwelling-units-a-solution-for-affordable-housing-in-your-own-backyard/. February 5.

- Saenz, Hunter. 2021. “Charlotte could eliminate single-family only zoning.” WNCN Charlotte. https://www.wcnc.com/article/money/markets/real-estate/charlotte-single-family-zoning-ordinance/275-71e61941-2e39-4f0e-9235-8b3c2d0a903e. March 2.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2008. “Accessory Dwelling Units: Case Study.” Huduser.com. https://www.huduser.gov/Publications/PDF/adu.pdf.

- Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. 1926. 272 U.S. 365. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/272/365/.

- Wegmann, Jake. 2020. “Death to Single-Family Zoning…and New Life to the Missing Middle.” Journal of the American Planning Association. 86(1): 113-119.

- Wright. “8 Modern In-Law Units.” Dwell.com. https://www.dwell.com/article/modern-in-law-units-47b11279.

- Yerena, Anaid. 2020. “Not a Matter of Choice: Eliminating Single-Family Zoning.” Journal of the American Planning Association. 86(1): 122-122.